Julia Kosulnikova “What Goes On In a Young Girl’s Mind?”

What goes on in a young girl’s mind? Over the history of humanity this question probably appears as the most frequently asked by the stronger sex. Questions as “What is to be done?”, “Who is to blame?”, and “Where’s the money coming from?” arise later. As we observe the works of Julia Kosulnikova, a youthful, pretty post-nymphet we ask ourselves this question, on both theoretical and practical levels. A young girl stained with paint give the same answers as a real young girl would: “Sweet beasties” “Blood? No, there’s no blood there…”; “Yes, I like The Middle Ages”. I always considered Russia as a country of permanent Middle Ages (thesis developed in the last years by Sorokin) but Julia’s subject is different. It’s not Ivan the Terrible’s pathetic orthodoxy, but a normal sado-masochistic Gothicism (plus early Renaissance) that we all have loved since Barbara and Sebastian sweet torments, Cranach’s dreams, Botticelli and Rogier van der Weyden, who is her favorite painter. And the last question is: after seeing all that, are you ready to surrender to Julia Kosulnikova (provided that she agrees)? Yes, it’s easier to buy off.

What goes on in a young girl’s mind? Over the history of humanity this question probably appears as the most frequently asked by the stronger sex. Questions as “What is to be done?”, “Who is to blame?”, and “Where’s the money coming from?” arise later. As we observe the works of Julia Kosulnikova, a youthful, pretty post-nymphet we ask ourselves this question, on both theoretical and practical levels. A young girl stained with paint give the same answers as a real young girl would: “Sweet beasties” “Blood? No, there’s no blood there…”; “Yes, I like The Middle Ages”. I always considered Russia as a country of permanent Middle Ages (thesis developed in the last years by Sorokin) but Julia’s subject is different. It’s not Ivan the Terrible’s pathetic orthodoxy, but a normal sado-masochistic Gothicism (plus early Renaissance) that we all have loved since Barbara and Sebastian sweet torments, Cranach’s dreams, Botticelli and Rogier van der Weyden, who is her favorite painter. And the last question is: after seeing all that, are you ready to surrender to Julia Kosulnikova (provided that she agrees)? Yes, it’s easier to buy off.

Artemy Troitsky

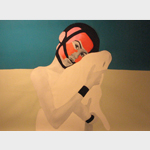

Julia Kosulnikova, a very young and quiet artist, is presented in D137 Gallery of Contemporary Art. The exhibition comprises works from two periods: 2007 and autumn of 2008. Big paintings of women prevail in both periods. Paintings go without titles and only speak the language of pictorial plastic. All the heroines are kept within bounds of a myth, they are either portrayed as animals (cows, deers etc.) or wearing masks of totem animals. However, it’s neither an ethnographic reconstruction inspired by a museum collection nor an illustration of ancient legends. Adequacy and modern meaning of this ethnographic imagery are clear. In wide black and white stripes on a blue cow mask, one can recognize a special geometry of traffic signs that gives notice of a traffic ban or a traffic route. The artist’s own body and an animal’s body next to her come under fires of red, white and black lines like a topographer covering the ground with a colorful net or an airdrome falling under a spotlight. The next period includes works of “the second phase”: objects and subjects interacting with an heroine. Of all the paintings of this period, stand out, the two most bizarres. In the first one, there is a human torso and hips, smooth and gray as stone, that leans on the top end of the painting and passes into a knuckle in the low end of the composition, reminding of a fleeced with moss rock that stands in a red desert. In the second painting, there is a body of a seated woman pierced by blue skeleton lines similar to aerial or homogenized veins that, in certain movies, connect growing bodies of aliens and constitute some sort of matrix. These pictures are acts of taming of art in which an automatic connection with a myth matrix is shown. Here happens an original marking of the world which, for everybody, starts with exploring their own body: transformed into pictorial frames it is a rare and powerful sight.

Julia Kosulnikova, a very young and quiet artist, is presented in D137 Gallery of Contemporary Art. The exhibition comprises works from two periods: 2007 and autumn of 2008. Big paintings of women prevail in both periods. Paintings go without titles and only speak the language of pictorial plastic. All the heroines are kept within bounds of a myth, they are either portrayed as animals (cows, deers etc.) or wearing masks of totem animals. However, it’s neither an ethnographic reconstruction inspired by a museum collection nor an illustration of ancient legends. Adequacy and modern meaning of this ethnographic imagery are clear. In wide black and white stripes on a blue cow mask, one can recognize a special geometry of traffic signs that gives notice of a traffic ban or a traffic route. The artist’s own body and an animal’s body next to her come under fires of red, white and black lines like a topographer covering the ground with a colorful net or an airdrome falling under a spotlight. The next period includes works of “the second phase”: objects and subjects interacting with an heroine. Of all the paintings of this period, stand out, the two most bizarres. In the first one, there is a human torso and hips, smooth and gray as stone, that leans on the top end of the painting and passes into a knuckle in the low end of the composition, reminding of a fleeced with moss rock that stands in a red desert. In the second painting, there is a body of a seated woman pierced by blue skeleton lines similar to aerial or homogenized veins that, in certain movies, connect growing bodies of aliens and constitute some sort of matrix. These pictures are acts of taming of art in which an automatic connection with a myth matrix is shown. Here happens an original marking of the world which, for everybody, starts with exploring their own body: transformed into pictorial frames it is a rare and powerful sight.

Ekaterina Andreeva